Psalm 139

O Lord, you have searched me and known me.

You know when I sit down and when I rise up;

you discern my thoughts from far away.

You search out my path and my lying down,

and are acquainted with all my ways.

Even before a word is on my tongue,

O Lord, you know it completely.

You hem me in, behind and before,

and lay your hand upon me.

Such knowledge is too wonderful for me;

it is so high that I cannot attain it.

Where can I go from your spirit?

Or where can I flee from your presence?

If I ascend to heaven, you are there;

if I make my bed in Sheol, you are there.

If I take the wings of the morning

and settle at the farthest limits of the sea,

even there your hand shall lead me,

and your right hand shall hold me fast.

If I say, “Surely the darkness shall cover me,

and the light around me become night,”

even the darkness is not dark to you;

the night is as bright as the day,

for darkness is as light to you.

For it was you who formed my inward parts;

you knit me together in my mother’s womb.

I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.

Wonderful are your works;

that I know very well.

My frame was not hidden from you,

when I was being made in secret,

intricately woven in the depths of the earth.

Your eyes beheld my unformed substance.

In your book were written

all the days that were formed for me,

when none of them as yet existed.

How weighty to me are your thoughts, O God!

How vast is the sum of them!

I try to count them—they are more than the sand;

I come to the end—I am still with you.

O that you would kill the wicked, O God,

and that the bloodthirsty would depart from me—

those who speak of you maliciously,

and lift themselves up against you for evil!

Do I not hate those who hate you, O Lord?

And do I not loathe those who rise up against you?

I hate them with perfect hatred;

I count them my enemies.

Search me, O God, and know my heart;

test me and know my thoughts.

See if there is any wicked way in me,

and lead me in the way everlasting.

In the late eleventh century, a thought popped up in Anselm of Canterbury’s head. Initially, he thought of it as a silly, passing thought, not worthy of further pondering, much less writing down. But this thought stuck in his head, distracting him from his occupations. It was the ontological argument for God’s existence; and, as if divinely inspired, Anselm prayerfully wrote it down. Before Anselm was an apologist, he was a theologian. This odd argument seemed to combine the two, proving God’s existence through human thought’s description of God. Many apologetic arguments already existed: the First Cause and cosmological arguments traced back to Greek philosophy, and arguments for Jesus’ resurrection appeared shortly after the event itself. This thought entered the tradition through its seemingly out-of-the-blue appearance to a medieval monk. Once it appeared, it never left.

If you are unfamiliar with this argument, I suggest you check out these three resources. Briefly, the argument defines God as the greatest possible being imaginable. It then states that God exists in the mind, as a concept. Something that exists in both the mind and in reality is greater than something that exists only in the mind. Thus, if God (defined as the greatest possible being imaginable) exists in the mind, God must also exist in reality–after all, God would not be the greatest possible being imaginable if God only existed in the mind! This is a simplified version of the complete argument, so I highly advise you to check out the above listed resources on the ontological argument.

When I first read the ontological argument, I thought it a fanciful wordplay. Many decry the ontological argument as an unsound argument. Others find its logic distastefully rigid. Thomas Aquinas pointed out that humans cannot quite wrap their minds around the nature of God. Kant disputed the idea that something existent is necessarily better. Gaunilo of Marmoutiers, a contemporary of Anselm’s, used reductio ad absurdum to argue that the ontological argument could be used on anything to arrive at absurd conclusions. But in spite of all the criticism it receives, and in spite of its confusing presentation, the argument is hard to forget once heard. The ontological argument stays cool, always reminding us, if only in whispers: “A fool says in his heart, ‘there is no God.’”

I still have difficulty fully wrapping my mind around the argument, but over the years since my first acquaintance with it, I have grown a respect for it. The ontological argument teaches that before one even thinks of the greatest good (God), it already exists in reality. This is beautiful, and, on many fronts, sound theology.

Good theology ascribes to God complete self-sufficiency. God is the essence of existence; He exists before anything else, and He caused all things “that were made to be” (John 1:3). When Moses asks God for His name, God responds, “I am that I am.” God’s name, יהוה (YHWH), is a conjugation of the Hebrew verb “to be; to cause to exist.” The ontological argument is more than a wooden syllogism. It sits at the core of much of man’s yearnings–and need–for God.

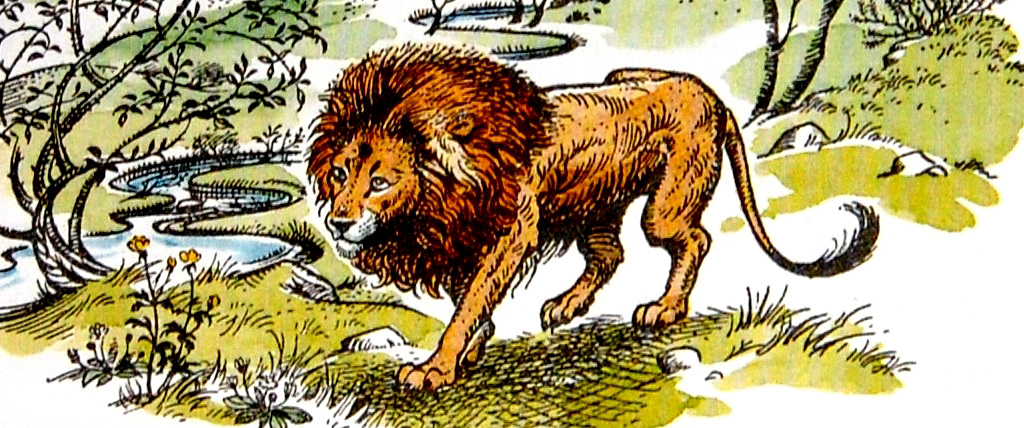

This belief that all things in existence could not exist without God results in a strong belief in the ultimate triumph of Good over Evil. Even when reality appears hopeless, God is our hope; at such times, only the Fool despairs at the loss of the greatest good, saying “There is no God.” J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis understood this well. At the climax of Lewis’s The Silver Chair, Eustace Scrubb, Jill Pole, Puddleglum, and Prince Rilian are stuck in the realm of the Queen of the Underland, a witch. (Lewis, in a letter about this scene, noted that he had “put the ‘Ontological Proof’ in a form suitable for children.”) The witch sprinkles a green powder into a fire to give the four travelers a sleepy feeling and keep them from thinking clearly. She then tries to convince them that the greener lands under the sun and Aslan himself are silly fairy tales that adults should consider fiction. Only her realm–the cold lamplight and the caves they see around them–only this exists. Puddleglum remains true to Narnia, giving a vivid description of his memories: “I’ve seen the sky full of stars. I’ve seen the sun coming up out of the sea of a morning and sinking behind the mountains at night. And I’ve seen him up in the midday sky when I couldn’t look at him for brightness.”

Even so, the witch pushes against the existence of such a beautiful world. She calls the ideas of the sun and Aslan “foolish dreams”: “You have seen lamps, and so you imagined a bigger and better lamp and called it the sun. You’ve seen cats, and now you want a bigger and better cat, and it’s to be called a lion. Well, ’tis a pretty make-believe… And look how you can put nothing into your make-believe without copying it from the real world, this world of mine, which is the only world… There is no Narnia, no Overworld, no sky, no sun, no Aslan.”

Ironically, Puddleglum remains clear-headed and saves his fellow companions from falling for the deceits of the witch. He counters, “Suppose we have only dreamed, or made up, all those things—trees and grass and sun and moon and stars and Aslan himself. Suppose we have. Then all I can say is that, in that case, the made-up things seem a good deal more important than the real ones. Suppose this black pit of a kingdom of yours is the only world. Well, it strikes me as a pretty poor one. And that’s a funny thing, when you come to think of it. We’re just babies making up a game, if you’re right. But four babies playing a game can make a play-world which licks your real world hollow. That’s why I’m going to stand by the play-world. I’m on Aslan’s side even if there isn’t any Aslan to lead it. I’m going to live as like a Narnian as I can even if there isn’t any Narnia. So, thanking you kindly for our supper, if these two gentlemen and the young lady are ready, we’re leaving your court at once and setting out in the dark to spend our lives looking for Overland. Not that our lives will be very long, I should think; but that’s small loss if the world’s as dull a place as you say.”

Interestingly, Aslan’s existence had been called a fairy-tale to Prince Rilian’s father, Caspian. When only a young boy, Caspian’s uncle tells him, “never let me catch you talking—or thinking either—about all those silly stories again.” But Caspian says, “All the same, I do wish.”

In Tolkien’s The Return of the King, Sam and Frodo are separated in Mordor, the dark and desolate land of Sauron. Alone in Mordor, surrounded by ash and smoke, Samwise Gamgee holds to a similar conviction and sings the following song:

In western lands beneath the Sun

the flowers may rise in Spring,

the trees may bud, the waters run,

the merry finches sing.

Or there maybe ’tis cloudless night

and swaying beeches bear

the Elven-stars as jewels white

amid their branching hair.

Though here at journey’s end I lie

in darkness buried deep,

beyond all towers strong and high,

beyond all mountains steep,

above all shadows rides the Sun

and Stars for ever dwell:

I will not say the Day is done,

nor bid the Stars farewell.

The beauty of Anselm’s ontological argument is that it not only proves the existence of God, but it describes this proven God as the greatest being imaginable. Both Puddleglum and Sam take Anselm’s ontological argument a step further, describing worlds more beautiful than the dark places they find themselves stuck in. Evil cannot exist independently, without God. The darkest evils will one day end their deceits, for even they owe their existence to God, Who is the greatest good imaginable. The more we see and ponder God’s goodness, the better we can bring Heaven to Earth and enter into the consummation of the Creator with His Creation.

Leave a Reply