Socrates is the beloved father of western philosophy, but I have found that many people discuss only part of his philosophy—that true wisdom is awareness of one’s own ignorance. Many stop at Socratic irony, glossing over another central theme of Socrates’ dialogues: the role of the gods in the guidance of ignorant human beings. Indeed, this theme is a necessary part of Socrates’ formula in his understanding of the world, for Socrates does think that men have a shot at attaining truth, despite their pathetic state of ignorance. Socrates’ own interpretations of his personal experiences of divine revelation give us an understanding of this aspect of his philosophy. I will begin this article by pointing out the missing link in our contemporary understanding of Socratic philosophy—the centrality of the divine in human understanding. Through Socrates’ life story as told in The Apology, his mysterious daemon, and his beliefs concerning virtue and the gods, Socrates makes it clear that anything and everything he knows—including knowledge of his own ignorance—comes from the gods.

An oft-ignored aspect of Socrates’ life is the centrality of religious observance and reverence for the divine. Meno concludes that all virtue comes from the gods; in The Apology, Socrates bears an uncanny resemblance to a martyr defending his life’s mission of proselytization; throughout his dialogues, he possesses a daemon that guides all his steps. When, in the classic Socratic worldview, humans fall short of understanding, Socrates often defaults to the gods as the givers of knowledge. To be sure, Socrates’ understanding and devotion to the gods was not the mainstream contemporary understanding, but he is nonetheless infused with a deep respect, even a fiery passion, for the gods. In “Socrates and the Divine Signal according to Plato’s Testimony: Philosophical Practice as Rooted in Religious Tradition,” Luc Brisson writes, “Socrates is immediately situated in a religious context which, consciously or unconsciously, contemporary commentators do not take into consideration” (Brisson, 9). The role of these religious experiences and Socrates’ own interpretations of them are essential to turning Socrates from a commoner into a philosopher. Ever since he received news from the oracle of Delphi, he left his normal, “unexamined” life and led the life of a radical philosopher, willingly living in poverty to further the divine directive he believed Apollo had given him. Yet, as Brisson observes, modern philosophers have in large part taken out this central theme of Socrates’ life, choosing rather to focus only on one part of the formula of his worldview—Socratic irony.

This is a mistake, however, as Socratic irony by itself is not in line with Socrates’ many dialogues that genuinely seek truth; contact with the divine is a theme in Socrates without which his worldview is nihilistic—something that Socrates does not show himself to be in dialogues such as Meno and Phaedo. Socrates believes that humans are not wise, but he nonetheless considers knowledge and wisdom to be worth pursuing. After all, he is famous for saying, “An unexamined life is not worth living” (38a). In Meno, he argues that understanding comes from the gods (99c-100b), and, in Phaedo, he speaks extensively of an afterlife myth (110b-115a). While no human is wise in his own right, those who are wise are wise because the gods have gifted them. Although Socrates claims ignorance, he can nonetheless be found in his dialogues trying with genuine intention to find the truth of the matter at hand. He often does not find the truth, but comes to various conclusions that tell us about this other part of the recipe of his worldview: the relevance of the gods to human wisdom. In this sense, Socrates is not unlike other pivotal figures of history—figures such as Jesus and Confucius—who criticized the establishment of their day without claiming that all hope for human wisdom is null. Thus, to understand Socrates, it is important—indeed, crucial—to examine his divine revelations and his own interpretations of them. Socrates does not believe in the value of human wisdom, but it would be wrong to say that Socrates holds no opinion with conviction. What gives Socrates his conviction is not human reason but divine revelation and his interpretation thereof.

In The Apology, as part of his defense, Socrates speaks of the transforming experience that resulted from the oracle of Delphi. Socrates’ piety and concern for the gods is apparent from the beginning of his story: “I shall call upon the god at Delphi as witness to the existence and nature of my wisdom, if it be such” (20e-21a). Importantly, Socrates did not by any means hear the oracle directly. He hears it from Chaerephon, who in turn hears it from the Pythian; and, of course, only the Pythian hears it directly from Apollo. Nonetheless, Socrates takes the oracle to heart and seeks a viable interpretation of the oracle. Instead of simply taking it as a straightforward, literal statement that Socrates is the wisest man on earth, he thinks about what it might mean for human wisdom in general—for, after all, he knows that he is not a wise man. He ask himself: “Whatever does the god mean? What is his riddle? I am very conscious that I am not wise at all; what then does he mean by saying that I am the wisest? For surely he does not lie; it is not legitimate for him to do so” (21b). Thus, Socrates set out to solve the riddle. He did so—in his classic Socratic manner—by trying to prove himself less wise than others whom the world considers wise. In this manner he went about, doing his best to understand what the god meant, until at last he took a step back and realized that, in his own words, “I am likely to be wiser than he [who thinks himself wise] to this small extent, that I do not think I know what I do not know” (21d). Here is the famous Socratic irony: no human is wise, but Socrates is the wisest of men only because he is aware of his own ignorance.

Yet it must be noted that even this realization was a gift from the gods. Apollo, to Socrates’ surprise, says that no man is wiser than Socrates, setting Socrates on his mission to find the truth behind this oracle. With this god-inspired realization, Socrates is filled with a passion to tell his fellow Athenians of the groundbreaking idea that only the man who knows he is not wise is, relatively speaking, wise. Socrates proceeds to give up the life of a normal citizen and contents himself with the bare minimums: “Because of this occupation, I do not have the leisure to engage in public affairs to any extent, nor indeed to look after my own, but I live in great poverty because of my service to the god” (23b). He speaks with people at the Agora with piercing criticism and a passion that gains him a reputation painted over by slander from the annoyed—a wide range of citizens, from Aristophanes to poets to craftsmen and many other troubled onlookers. Despite this, he stayed on his mission to “come to the assistance of the god” (23b) and reveal the human state of ignorance to those who think themselves wise.

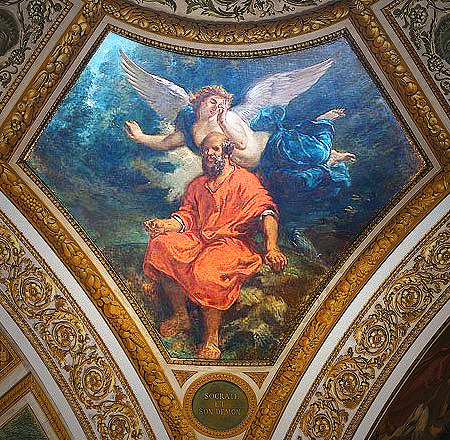

Socrates also references in various dialogues his divine signal. He refers to his divine signal in a few different dialogues, but its nature remains mysterious and, simply put, baffling. Often called his daimon, it is generally understood to be some form of a minor deity. This divine signal is no guardian angel, but, rather, comes from an unspecified divine being. Brisson suggests that the signal “could have been sent to Socrates by Apollo or by any other divinity of the traditional pantheon” (4). In The Apology, Socrates appears to contradict himself when he speaks of death: when speaking to the general assembly, he says, in the self-admitting ignorance so iconic of Socrates, “No one knows whether death may not be the greatest of all blessings for a man” (33); but later he tells his friends that “What has happened to me may well be a good thing, and those of us who believe death to be an evil are certainly mistaken. I have convincing proof of this, for it is impossible that my familiar sign did not oppose me if I was not about to do what was right” (43). While many contemporary scholars of Plato (T.C. Brickhouse, N.D. Smith, and Mark A. Joyal) take issue with this seeming contradiction, Brisson points out that Socrates could be referring to “good” and “bad” results in different ways, depending on the context. Moreover, Brisson points out that, because the gods ensure that “a good man cannot be harmed either in life or in death, and that his affairs are not neglected by the gods” (41c-d), and Socrates considers himself a good man, Socrates must by his firm religious belief interpret his death penalty as a good thing.

I propose a similar approach: Socrates, when speaking in front of the crowd, held an undecided opinion on the merits of death, but, only after some time for reflection and interpretation of the results of the divine signal, Socrates came to the conclusion that death is not a bad thing in his context. Typical of Socrates, he does not assume that he (or any other human, for that matter) knows the truth about death—that is, until he has the opportunity to interpret divine revelation, his “familiar prophetic power” (40a). When divine revelation is added to the picture, his attitude changes and he sees such revelation as the ultimate source of wisdom for humans, making sure to follow it as best he can to the last command.

Passages from Meno further confirm the importance of divine influence in Socrates’ philosophy. Although Socrates never actually comes to a concise definition of virtue, he concludes in Meno that virtue does not come from human wisdom but, rather, it is a gift of the gods. He first argues that virtue is not inherent or natural to humans—that is, no one is born virtuous—and that virtue is not something humans can teach each other or learn from each other (99a). When we think of a good person, we must understand that he is neither good because he was born that way or because of instruction. Rather, Socrates stresses, virtue “comes to those who possess it as a gift from the gods which is not accompanied by understanding” (100a). This idea that virtue comes from the gods is not an insignificant supplement to Socrates’ philosophy; it is a central part of his goal in Athens. In the last two sentences of Meno, Socrates tells Meno to speak to Anytus (who later prosecuted Socrates in The Apology), saying, “You convince your guest friend Anytus here of these very things of which you have yourself been convinced, in order that he may be more amenable. If you succeed, you will also confer a benefit upon the Athenians” (100b). It must be noted that the result this command leads to is the same as Socrates’ own life goal as a philosopher: to confer a benefit upon the Athenians. Not only with Socrates’ conclusion that virtue comes not from man but from the gods, but also with his command for Meno to tell others “these very things” (100b), Meno shows us the centrality of the divine in Socrates’ philosophy.

Socrates treats the divine as central to the source of the most desirable wisdom and admits that human wisdom is on a completely different level from knowledge that emanates from divine sources. His emphasis on the gods as a source of wisdom goes hand-in-hand with his understanding that the ultimate source of truth lies in the hands of the divine.

Leave a Reply