This is the third installation in a series of articles in which I present my view of church history with a focus on the relationship between church and state. In my last article, I covered the caesaropapism. Today I cover the middle ages, the Holy Roman Empire, and the papacy. In my next and last installation, I will cover the reformation.

By no means does this series provide a comprehensive history. This article covering the middle ages does not even mention Charlemagne, Pepin’s reforms, Wycliffe, or the Hussites. Rather, I have chosen to focus on a small number of events I see as emblematic of their time.

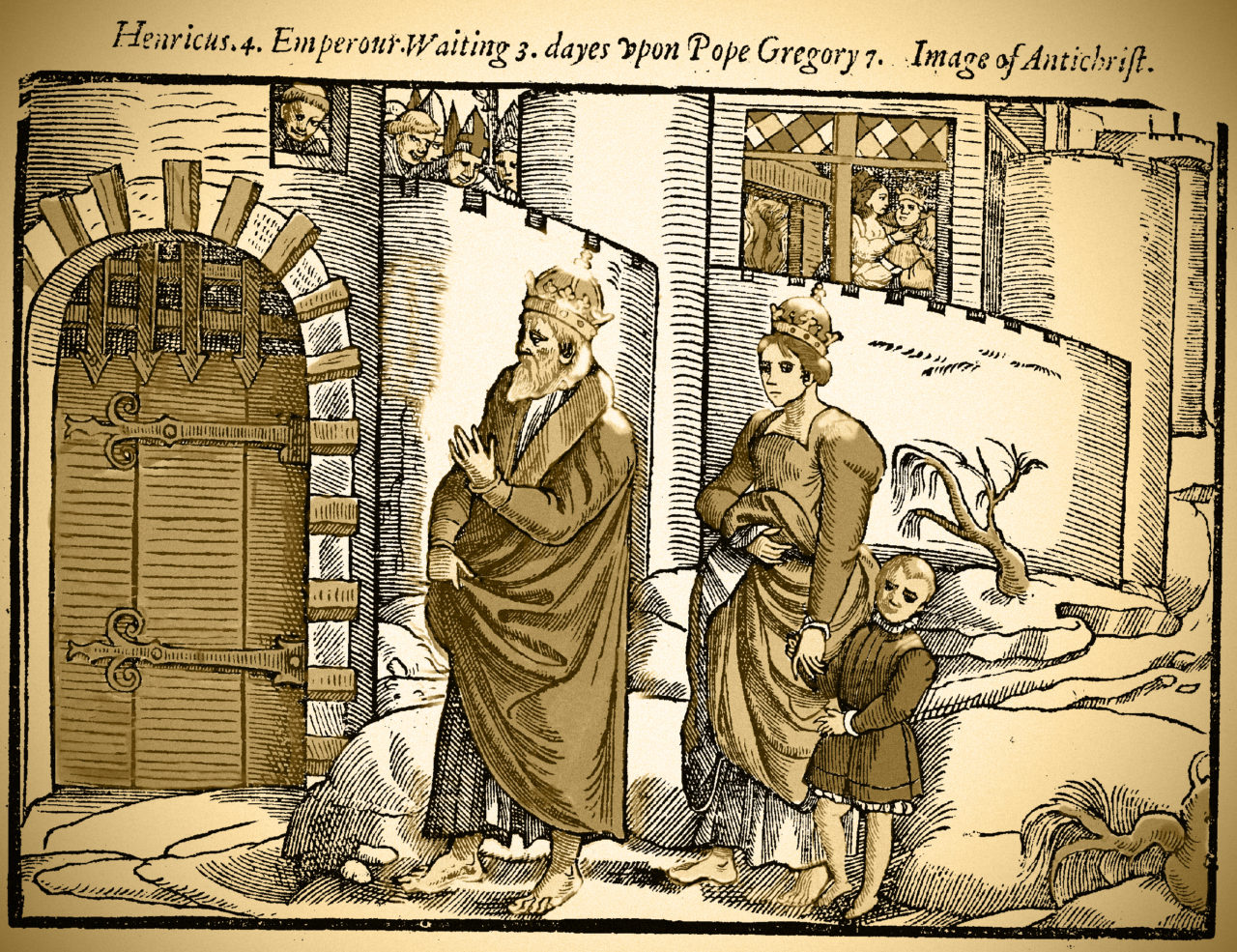

In 1076-1077, a turbulent series of events put forth the Pope as authority over the Emperor in matters of the church. Traditionally, the investiture of bishops was a privilege of the Holy Roman Emperor, but Pope Gregory issued a papal decree that offered reforms for this system, taking away the Holy Roman Emperor’s ability to install bishops. Henry IV, the Holy Roman Emperor, was enraged at this, and he renounced Gregory VII as Pope. In return, Gregory excommunicated Henry, and, in his Lenten Synod of 1076, took away his kingship. This punishment was to become permanent after one year. And so came the famous story of how Henry IV, the Holy Roman Emperor humbled himself before Pope Gregory VII.

In January of 1077, before the deadline offered by the Lenten Synod had been reached, Henry IV made his walk from Spyre, Germany to the Pope’s residence in Canossa Castle, in northern Italy. When he reached the Castle, the doors were closed and Henry IV was locked out in a raging January blizzard. So Henry IV fell to his knees and humbled himself before the Pope for three days and three nights. Finally, Pope Gregory came out and received him, revoking the excommunication of Henry IV—and, of course, reinstating him as Holy Roman Emperor. Thus is the story of how the throne in 1077 bowed to the Pope. Of course, one may rightly argue that the Pope had the right to install his own bishops, and the state had no business in the matter. While this argument may be an oversimplification, it does have its merit. The significance of this story, however, was not about the power the Pope won in being able to install his own bishops; rather, it concerned the display of power the Pope showed in Henry IV’s act of humility. Yet, even in this major act of international obeisance, the matter still remained one of the pope, the monarch, and the bishops. The church, if one is to include the priests, was not necessarily at unified conflict with the king.

A few other similar showdowns occurred between church leader and monarch. In 1170, the archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket was killed for his excommunication of church enemies. He had had a history of struggle with King Henry II of England, and, when Henry III (better known as Henry the Young King) visited him, the young prince found more love in Thomas Becket than he did in his own father. However, when the time came for Henry III’s coronation, Thomas Becket did not crown him: rather, two bishops and an archbishop did so. As England’s first home for Christianity, Canterbury was a central cathedral for the English, and the archbishop of Canterbury would traditionally crown the monarch. Thomas Becket poured his wrath on the bishops and archbishop, excommunicating them, and continued to excommunicate other people in the church he deemed his enemies. When Henry the Young King heard of this, he displayed his distaste for Thomas Becket, and, in a disputed order, implied to his knights that he wanted Thomas Becket gone. Four of his knights proceeded to the Canterbury Cathedral and, while Thomas Becket was praying, killed him in the Cathedral. The blood spilled on holy ground backfired for the monarch, however, and Thomas Becket is now considered a martyr-saint by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Church.

In the thirteenth century, a string of popes came about who greatly expanded the role of the church into the realm of secular matters. Innocent III continued the “tradition” of disputes be tween the local king and the international pope on the appointment of bishops. His dispute with King John of England was over the appointment of the Bishop of Canterbury. This story, however, brings in for a short period a third party that has often been ignored: the local church, as opposed to the international church leader. King John pushed forward for John de Gray, while the local clergy of Canterbury wanted Reginald. This dispute continued, and the Canterbury clergy secretly elected Reginald as bishop, sending him to Rome for confirmation. When King John found out, however, he managed to reverse the decision, forcing the Canterbury clergy to choose John de Gray. Innocent III, however, favored Stephen Langton, one of his fellow students in Paris. [1] But, even after King John refused to go forward with Innocent’s desire for Langton to become bishop, Innocent nonetheless went forward with it and consecrated him as Bishop of Canterbury. King John became infuriated and would not let Langton in England. He seized Church property in England; in response, Langton threatened excommunication. However, the use of excommunication as a means of papal punishment had already been dimmed in King John’s eyes, as this had already happened to two of his close friends: his brother-in-law, Raymond VI of Toulouse, and his nephew, Emperor Otto. King John, perhaps, sought political independence from the strings of the papacy, and in so doing tried to make the Catholic Church in England obey the king over the pope. Innocent saw himself as freeing the Catholic Church in England from King John’s political grip. Much as Hitler has become the embodiment of evil for modern writers, Pharaoh used to hold the position of the oppressive monarch of bondage. In a letter to King John, Innocent wrote:

by the example of Him who with a strong hand freed His people from the bondage of Pharaoh, we intend with a mighty arm to free the English church from your bondage: and we now truthfully and firmly forewarn you that, if you will not accept pace when you may, you may not when you will, and repentance will be useless after your downfall—as you may learn from the instances of those who in your own time have acted with a similar presumption. [2]

King John did not give in to the pope, and he was excommunicated. Not until 1213 did King John reconcile a deal with Innocent III. While Innocent III may have won out on this one, the use of excommunication to punish those who opposed the papacy became more and more common, and, in so doing, less and less potent. The excommunication of Henry IV prompted an immediate radical act of humility from the Emperor, but this time it took King John four years to resolve the excommunication.

But Pope Innocent did not only command a strong authority in the realm of choosing bishops of other countries. With the waxing of the papal authority, Europe proceeded to execute the Fourth Crusade that Innocent III had called for. The plan was originally to take Jerusalem by going through Egypt, but this fell through and the crusaders passed through Constantinople instead. Along the way, they sacked the city. This went against Innocent’s commands, but the Pope nonetheless conveniently dubbed it as God’s will, and the Crusade continued. The sacking, however, soured the relationship of the western and the eastern churches.

Just over a decade later, in 1215, he called together the Fourth Lateran Council, an ecumenical council with widespread attendance by bishops from both the east and the west. Four hundred and four bishops came, although the Greek bishops of the Patriarchate of Constantinople did not heed Innocent’s request to attend. Still, the wide attendance included bishops from Bohemia, Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, and Estonia. The Council went over various church reforms, heresy (especially the Carthar heresy), unification of the Holy Roman Empire (including the confirmation of Frederick II as Emperor), and a call for crusades. The Cathari of Southern France held a dualism repugnant to the Church, and this prompted the defensive war against them in the form of the Albigensian Crusade. Legislation was made for Jews to wear “a distinctive dress” and not to be allowed to appear in public during Holy Week. To quote Hubert Jedin, “With Innocent III, the medieval Papacy reached the climax of its spiritual and secular authority.” Yet even this did not mean that the Church itself did as a whole: the bishops were not always in agreement with the Pope, and multiple layers of controversy arose from within the church. “Nevertheless,” writes Jedin, “the fourth Lateran Council was not by any means a mere ‘display of absolute papal mastery over the universal Church’, nor were the bishops ‘degraded to the role of mere tools of an almighty Pope’, as Heiler would have it. Even Innocent III did not have his way all the time.” [3] The power Innocent III displayed during his papacy was purely papal power, and did not apply to the church as a whole. A distinction of both power and priority existed and persisted between the local bishops and the papal authority.

[1] Hans-Georg Beck, et al, History of the Church IV: From the High Middle Ages to the Eve of the Reformation (Seabury, 1980) 137.

[2] W. H. Semple, Selected Letters of Pope Innocent III concerning England (1198-1216) (Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1953), 131-132.

[3] Hubert Jedin, Ecumenical Councils of the Catholic Church: An Historical Outline (Herder and Herder 1960), 80.

Leave a Reply