She spoke a language I could not understand. Standing a few inches taller than me, with dark hair tied up in a tight ponytail and her arms crossed, this young, bright poli sci student looked me in the eye and said, “I feel so sorry for you.” I gaped. The smile that accompanied these words signalled pity, but not, I thought to myself angrily, compassion.

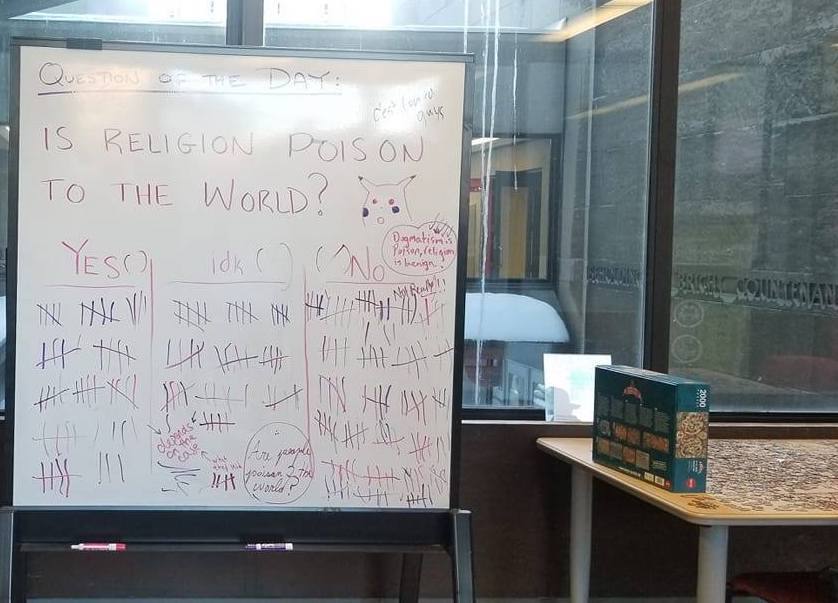

We stood by a table in the library hall. My apologetics team had propped up a poster with the question of the day (“Is religion poison to the world?”), and my new friend, attracted by the incendiary question, quickly engaged two of us in conversation. We spoke for over an hour. I felt my cheeks grow hot, and my voice took on an increasingly indignant tone as I realized this girl was here to speak, but not to listen. She unraveled my arguments, made herself a defender of the silenced and the marginalized. I became the Church, and the Church became God, and “God” became a narrow-minded, ignorant system of rules, driven by blind obedience and cushioned by naive concepts of love. With some impatience, I tried to separate God from His representatives. I talked about God’s compassion. I talked about His forgiveness. Somehow, we moved to the topic of homosexuality. That was when I said I believed not only the homosexual, but all of humanity, was broken. To this, the girl stiffly replied:

“See, I don’t get what you mean by that. I’m offended when you say that. I don’t think I’m ‘broken.’”

When we heard that declaration, my Christian friend and I mentally threw up our hands and thought, “This girl is a hopeless case.” What could we possibly do with someone who believed she did not need a Savior? Clearly, this girl was not what we call, in Christian lingo, “a seeker.” So we gave up. Once she left, we prayed for her, convinced only God could work a miracle in her life. I went home that day and promptly banished our uncomfortable discussion from my thoughts. But what I did not realize was my own prejudice. I did not acknowledge that I, too, wanted to speak and not listen. The girl spoke a language I could not understand, and I did not realize my language was just as foreign.

This morning, I listened to Rosaria Champagne Butterfield’s The Secret Thoughts of an Unlikely Convert for the first time. I expected to hear the story of a lesbian convicted of her sin and swept away by God’s grace (take note of my word choice). I found, instead, the story of an energetic, intelligent, funny lesbian who possessed a personal and carefully thought-out value system; who lived out what she genuinely believed to be a moral, radically compassionate and hospitable life; and who, over two years, encountered the compelling pull of the Christian God revealed in Scriptures. Even then, Rosaria notes that she did not completely understand “repentance.” “Guilt” and “shame,” familiar words in my everyday vocabulary, meant little to her. As Rosaria says (and I paraphrase), unbelievers do not struggle with sin. The idea is wholly Christian. However, Rosaria understood that this God business was important and impossible to ignore. Tentatively, she struck up a friendship with an elderly Christian couple, devoured the Bible as only an English professor and critical scholar can, and eventually surrendered her life to Jesus.

I am humbled to read Rosaria’s story. Though I never consciously vocalized this before, I do believe that, somewhere along the way, I began to think of unbelievers as unbelievers–that is, people without beliefs, without values, without morals. I thought this because, well, if people didn’t believe in what I believed, I must simply treat them as blank slates to be educated. And oh how tragic my mindset! When I come to the threshold of a different culture, and rap on the door, and say, “Struggler, behold your brokenness and your sin, and taste the freely offered forgiveness of the Lord!” — do I actually think I will be admitted? Will they open the door to words that are repulsive because they are foreign? What brokenness? What sin? Forgiveness for what?!

I am not saying, of course, that we are not broken, or that the lesbian and gay are not sinners. But what compelled Rosaria to convert was not “brokenness” or “sin.” These are the words a Christian might use. For Rosaria, it began with “need.” An undefined, elusive, very real need.

There is a place for talking about sin. It is a concept absolutely fundamental to the Gospel. But how do we talk about it? When do we talk about it? Rosaria writes that answers must come after questions. When someone like my poli sci friend comes up to me and says, “I am not broken,” the declaration does not mean “hopeless case.” It means we must adjust our words, and listen. Perhaps she is asking questions that I have not considered. It is very likely, almost certain, that I do not understand her. Will I be patient enough, and loving enough, to try? J. Dodson, a pastor from Austin, Texas, writes, “Instead of correcting [my friend’s] life choices, I needed to understand his choices.” Many of the people we encounter in life act upon convictions that they have thoughtfully, carefully arrived at (perhaps more thoughtfully and carefully than some of us Christians). They are trying to answer questions that I believe the Gospel can satisfy. But am I speaking a foreign language? Am I answering the wrong questions?

It is unhelpful to discourage an individual from pursuing their passions, if they do not have an alternate source of joy. It is dehumanizing to delegitimize their form of identity without showing them that they have been given a greater, concrete identity, having been created to know an all-wise, and all-loving Father.

G.H., “Stepping out; Breaking free“

Even now, I struggle with what I have laid out here. I think to myself, “But isn’t the Gospel offensive? Oughtn’t I to preach it as it is, regardless of my audience? To stick with the script (‘good God, broken humanity, loving Savior’)?” I think there is a place and a time for such directness. I think, too, that far exceeding the best of formulas for evangelism is the indispensable leading of the Holy Spirit. But sometimes, I wonder if there is a conversation, a divine appointment, a quietly growing friendship, where simply listening, praying, and striving to understand is enough. I wonder how we can be kind and generous without sacrificing or hiding the light of the Gospel. And I think about people like Rosaria Butterfield. Oh to learn humility, compassion, and radical hospitality! To share Jesus not because we are eager to be right, but because we have truly learned and understood the deepest longings of our friends, have ached to give them happiness, and have found a spring of water in the desert that can slake the thirst of every human soul.

Leave a Reply