[1] For those of you who attended the debate on creationism at the Morning Walk Convention in 2021, you may remember my violation of the debate format by bringing up a quote from Augustine. For those of you who were not there, the debate was a five-person event: two contenders for each side, a representative for each side, and an undecided moderator. As a representative for theistic evolution, I could not come up with any original arguments myself; that was the purpose of the contender. Instead, I was supposed to represent their view to the moderator and only add information as it relates to my contender’s point. However, in my preparation, I found a quote from Augustine that I thought would be good food for thought on how Christians should approach evolution (and a good number of other issues).

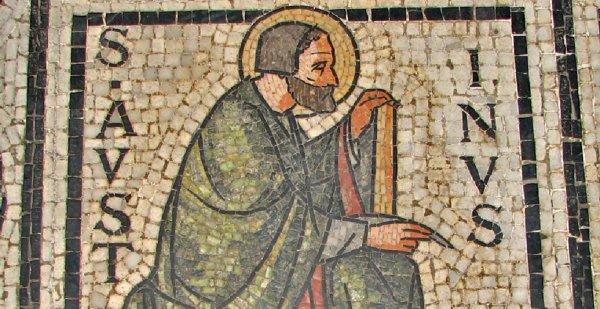

This quote is from Augustine’s The Literal Meaning of Genesis. Chapter 19 addresses some very pertinent points for Christians today on how staunch creationism can actually act against the Great Commission. I will break down the chapter into a few chunks for ease of digesting.

On interpreting the mind of the sacred writer. Christians should not talk nonsense to unbelievers. Let us suppose that in explaining the words, “And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and light was made,” one man thinks that it was material light that was made, and another that it was spiritual. As to the actual existence of “spiritual light” in a spiritual creature, our faith leaves no doubt; as to the existence of material light, celestial or supercelestial, even existing before the heavens, a light which could have been followed by night, there will be nothing in such a supposition contrary to the faith until un-erring truth gives the lie to it. And if that should happen, this teaching was never in Holy Scripture but was an opinion proposed by man in his ignorance. On the other hand, if reason should prove that this opinion is unquestionably true, it will still be uncertain whether this sense was intended by the sacred writer when he used the words quoted above, or whether he meant something else no less true.

Augustine starts with the rather strong jab at, well, us! I myself know that oftentimes my political or philosophical views dominate how I explain the faith. While I do sincerely hold my “of this world” beliefs, when trying to bring the Gospel to others I find these views can dominate to an unhealthy degree. Augustine raises the real concern that we risk conflating our personal views with the divine truths expressed in scripture. I need to step back and differentiate what beliefs are mine, and what are key doctrines that are scripturally based. Knowing that line is helpful in approaching conversations honestly and being clear when you speak from your own opinion and when you speak from the authority of scripture.

And if the general drift of the passage shows that the sacred writer did not intend this teaching, the other, which he did intend, will not thereby be false; indeed, it will be true and more worth knowing. On the other hand, if the tenor of the words of Scripture does not militate against our taking this teaching as the mind of the writer, we shall still have to enquire whether he could not have meant something else besides. And if we find that he could have meant something else also, it will not be clear which of the two meanings he intended. And there is no difficulty if he is thought to have wished both interpretations if both are supported by clear indications in the context.

This passage provides a helpful technique for identifying what beliefs are those core biblical doctrines and what beliefs may not be. When we are dealing with a passage that is being put under criticism, we need to start by looking to see what reasonable readings of the passage are possible. If we end up finding that several readings are possible, we should proceed with caution before pronouncing the correct reading. In the context of evangelism, it would make sense to not bother trying to understand every piece of scripture before our friend finds Christ. Instead of focusing on our sins, our need for God and Christ’s incarnation, death, and resurrection would be a more ideal starting place. For these more difficult passages, we can go to those with authority to try to decipher the meaning and have this discussion.

Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars and even their size and relative positions, about the predictable eclipses of the sun and moon, the cycles of the years and the seasons, about the kinds of animals, shrubs, stones, and so forth, and this knowledge he holds to as being certain from reason and experience. Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking non-sense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. The shame is not so much that an ignorant individual is derided, but that people outside the household of the faith think our sacred writers held such opinions, and, to the great loss of those for whose salvation we toil, the writers of our Scripture are criticized and rejected as unlearned men.

Augustine seems to fall into line, quite directly, with the main premise of Fides et Ratio, namely that knowledge attained by faith and knowledge attained by reason (of which science is a part) compliment each other. Their complementarity can be an asset in conversion; as one reaches out to the truth the other can agree with and bring them to a more full truth in Christ. However, a systematic rejection, or instinctive reaction against, “science” can prove damaging towards others’ salvation and lead them to, as Augustine says, reject the bible as naive and unhelpful.

If they find a Christian mistaken in a field which they themselves know well and hear him maintaining his foolish opinions about our books, how are they going to believe those books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven, when they think their pages are full of falsehoods on facts which they themselves have learnt from experience and the light of reason? Reckless and incompetent expounders of holy Scripture bring untold trouble and sorrow on their wiser brethren when they are caught in one of their mischievous false opinions and are taken to task by those who are not bound by the authority of our sacred books. For then, to defend their utterly foolish and obviously untrue statements, they will try to call upon Holy Scripture for proof and even recite from memory many passages which they think support their position, although “they understand neither what they say nor the things about which they make assertion.

In this last section from St. Augustine, we are warned against the misuse of scripture, which can have deleterious effects on the salvation of others. We should be careful of using scripture in conversation to voice our opinions, especially when speaking with non-Christians. From reading this section of Augustine I have two takeaways personally. First, I think it is important to prioritize the views we are advocating for in scripture. If, in a conversation, our views on the literal reading of Genesis stand in the way of someone following Christ, then we should prioritize Jesus first. Secondly, I believe humility to be a great asset in these conversations. I have been told (more than once by more than one person) that I sound more confident on many issues than I should. Knowing my own limits and that I am not the most knowledgeable on any topic can help demonstrate that when I get something wrong, it is not a big deal to be corrected.

So perhaps I am wrong in believing in an evolutionary take of God’s creation! Regardless of that, approaching such issues with humility, a focus on Christ, and openness to correction could do the debate good.

[1] My title was intentionally inflammatory. I know evolutionary theory did not exist at Augustine’s time and he would have likely not even considered the possibility. I do however think he would not have an issue being an evolutionist given current scientific evidence.

Leave a Reply