Several months ago I was speaking with someone (whom I can’t seem to remember!) about difficult passages in scripture. One passage that stuck out as something to spend more time wrestling with was the story in 2 Samuel 21 where David hands over the sons of Saul whom the Gibeonites kill. In this article I do not intend to write a definitive answer to those who wrestle with this passage; rather I wanted to present some thoughts I have had through both reading and conversation with the passage.

Now there was a famine in the days of David for three years, year after year; and David inquired of the Lord. The Lord said, “There is bloodguilt on Saul and on his house, because he put the Gibeonites to death.” So the king called the Gibeonites and spoke to them. (Now the Gibeonites were not of the people of Israel, but of the remnant of the Amorites; although the people of Israel had sworn to spare them, Saul had tried to wipe them out in his zeal for the people of Israel and Judah.) David said to the Gibeonites, “What shall I do for you? How shall I make expiation, that you may bless the heritage of the Lord?” The Gibeonites said to him, “It is not a matter of silver or gold between us and Saul or his house; neither is it for us to put anyone to death in Israel.” He said, “What do you say that I should do for you?” They said to the king, “The man who consumed us and planned to destroy us, so that we should have no place in all the territory of Israel let seven of his sons be handed over to us, and we will impale them before the Lord at Gibeon on the mountain of the Lord.” The king said, “I will hand them over.”

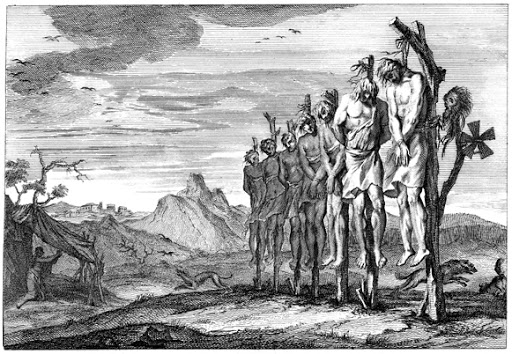

But the king spared Mephibosheth, the son of Saul’s son Jonathan, because of the oath of the Lord that was between them, between David and Jonathan son of Saul. The king took the two sons of Rizpah daughter of Aiah, whom she bore to Saul, Armoni and Mephibosheth; and the five sons of Merab daughter of Saul, whom she bore to Adriel son of Barzillai the Meholathite; he gave them into the hands of the Gibeonites, and they impaled them on the mountain before the Lord. The seven of them perished together. They were put to death in the first days of harvest, at the beginning of barley harvest.

Then Rizpah the daughter of Aiah took sackcloth, and spread it on a rock for herself, from the beginning of harvest until rain fell on them from the heavens; she did not allow the birds of the air to come on the bodies by day, or the wild animals by night. When David was told what Rizpah daughter of Aiah, the concubine of Saul, had done, David went and took the bones of Saul and the bones of his son Jonathan from the people of Jabesh-gilead, who had stolen them from the public square of Beth-shan, where the Philistines had hung them up, on the day the Philistines killed Saul on Gilboa. He brought up from there the bones of Saul and the bones of his son Jonathan; and they gathered the bones of those who had been impaled. They buried the bones of Saul and of his son Jonathan in the land of Benjamin in Zela, in the tomb of his father Kish; they did all that the king commanded. After that, God heeded supplications for the land. (2 Samuel 21:1-14)

This passage is a difficult one for a variety of reasons. First, it offends our western, post-enlightenment sensibilities to see people be punished for the sins of their ancestors which they did not commit. [1] Secondly, we see God directly involved with His word (and his authority) at the beginning. Then the decision power goes to David who passes on the final sentencing to the Gibeonites. So there exist several entities in the decision chain, two of which are sinful humans. Finally, there is the question of why the son of Jonathan, Mephibosheth, was spared and how this reconciles with justice.

In terms of the first question, “Was the killing of Saul’s children immoral?” there are two points of entry that I see where moral judgment could have lapsed. We see in 2 Samuel examples of David’s moments of weak leadership where he lets himself be run over by others. Absolom is the most pertinent example. Concerning the Gibeonites, it could be that David should have set the terms for the Gibeonites and decided what should be done in reparations without giving them the authority to decide. It could have also simply been the Gibeonites who bore responsibility for this action and should not have executed Saul’s children. [2]

If we understand the killing of Saul’s sons as good and just, how do we make sense of God’s justice as the slaughter of descendants who did not commit the sin their ancestors did? One explanation is that these sons of Saul did actively partake in the killing of Gibeonites in one way or another and did incur the same guilt themselves as Saul did. This explanation, while possible, seems like a cheap way to get out of the question by adding information that is not necessarily what actually happened. We simply may not be fully appreciating the wounding impact of sin generationally. We know sin has a generational impact and perhaps it is that the wicked seed of Saul needed to be cut out for the protection of Israel. [3]

Finally, if we believe that the killing of Saul’s sons was ordained by God, was it unjust that Jonathan’s son was allowed to live? Can the pact that Jonathan made with David to show kindness on his family extend to David, allowing Mephibosheth to escape just punishment? This could be an allowance of mercy by God through David, where Mephibosheth deserves to die for the sins of Saul but is allowed to live out of the generosity of David.

Ultimately, I left my dive into the Gibeonite reparations without a strong opinion to resolve all of these questions. Perhaps guilt is incurred even though they did nothing wrong and their deaths were justified. Perhaps it was wrong for David to spare Jonathan’s son (especially if he committed evils with the other sons of Saul). Maybe our focus on the fallen world we live in today conceals the true scope of where death fits into eternity, and the deaths of Saul’s sons were actually mercy in a way we do not understand. Regardless, wrestling with Scripture and not being able to answer every question provides a great opportunity to trust in God. Just as Isaac trusted his father Abraham when going to the sacrifice, we can trust our God because we know he loves us. Any lack of our understanding of the ways of the Lord does not take away the reality of God’s love for us and that love manifesting in Christ’s atoning sacrifice for our sins. These moments of “wrestling with God” are moments that can be celebrated as a time to trust him even when we do not know the way.

[1] Of course, there is the argument that they did commit these sins but that is not something immediately obvious from the text.

[2] When Shemei curses David in 2 Samuel 16, perhaps this refers to the killing of Saul’s sons?

[3] Personally I tend to lean away from this reading as it seems to be in tension with Ezekiel 18:1-25, which discusses why the righteousness of a son is not dependent on his father.

Leave a Reply