ZS wrote this two-part overview of Jewish martyrdom in 2018. We post it now with consideration of those who joined the ranks of kedoshim on October 7, 2023.

The concept of martyrdom within Judaism wrestles with several issues. Martyrdom carries different functions within Judaism, often changing with historical context. Judaism tries to set clear determinations for situations in which a martyr’s death is preferred, although this tends to be a difficult task with gray areas. A martyr receives rewards in haolam haba (“the world to come,” or the afterlife). Unlike Christian martyrdom, Jewish halakhah arguably focuses more on the action of martyrization than on the martyred individual. At the same time, the impact martyrdom makes on Jewish culture often depends on the legend of the martyred subject. At various points, post-Second Temple martyrs have been compared with temple sacrifices, making martyrdom intensely holy. As Jews faced different challenges through the ages, Jewish martyrdom morphed to counteract these challenges and keep alive Jewish identity. At the heart of this striving lies the fate God commands in Leviticus 22:32: “You shall not profane my holy name, that I may be sanctified among the people of Israel: I am the Lord, who made you holy.”

Before continuing, I first want to briefly discuss the terminology surrounding Jewish martyrdom. “Martyr” is at its core a Christian term meaning “witness.” Within Judaism, martyrs are called kedoshim, coming from the Jewish concept of Kiddush HaShem, which means “Sanctification of the Name.” The (often public) killing of a Jew for his Jewishness is interpreted by Jewish martyrology to sanctify God’s name. In rabbinic literature, martyrs are sometimes called tsadikim (“righteous ones”), coming from tsidduk hadin (“the justification of [God’s] verdict”). For the purposes of this essay, I will use two sets of terminology interchangeably: kedoshim with “(Jewish) martyrs”; and Kiddush HaShem with “(Jewish) martyrdom.”

The Historical Scope

To determine the historical scope of Jewish martyrdom, we begin with the Hebrew Bible. The Hebrew Bible contains no easily identifiable martyr stories. Saul and Samson’s deaths, in some ways, resemble martyrdom. While losing a battle with the Philistines, Saul asked his shield-bearer to slay him, “so that the uncircumcised may not run me through and make sport of me” (JPS; 1 Samuel 31:4). When his shield-bearer refused, Saul killed himself. Saul may have performed this act to deprive the Philistines the evil of abusing and torturing him (although they did subsequently make sport of his corpse). However, it seems Saul killed himself primarily to avoid his own humiliation. This does not constitute martyrdom.

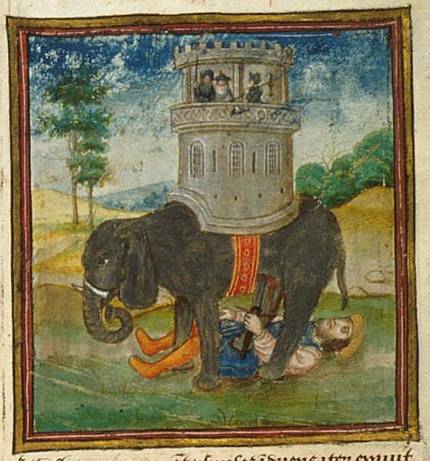

Samson’s death more closely resembles martyrdom. Blinded and humiliated by the Philistines in their temple, Samson asked God for a last surge of superhuman strength “to take revenge of the Philistines” (Judges 16:28). Knowing he would die with the Philistines, he brought down the two pillars that supported the temple. The narrator remarks that “those who were slain by him as he died outnumbered those who had been slain by him when he lived” (30). Samson willingly died in an act of revenge on his persecutors. At the same time, this was a sacrifice calculated to kill as many Philistines as possible, akin to Eleazar Avaran’s act of martial courage. [1] This can be interpreted either as a heroic move by a man of war or, more loosely, martyrdom; indeed, Samson’s death influenced later conceptions of martyrdom within Judaism. But the Biblical passage focuses on Samson’s military heroics, recounting the mass of dead Philistines. The text of Samson’s death only resembles a martyr story. It cannot be considered a foundational event that established martyrdom within Judaism.

The burning of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego would make for a good martyr story had the three not survived the furnace. The same applies to Daniel’s insistence on praying and his miraculous survival of the lions’ den. These stories come close to typical martyr stories, and they later do inspire ideas about martyrdom; indeed, Shadrach, Meshach, Abednego, and Daniel may be considered martyrs. But, taken in their Biblical context, these stories are about the miracles of survival.

Most scholars believe that the first recorded instances of Jewish martyrdom take place in 2 Maccabees. [2] Second Maccabees 6-7 describes a number of instances in which Jews were killed for their observance of Judaism. This follows the typical understanding of martyrdom. Today, Jewish martyrdom usually commemorates victims of anti-Semitic terrorism, such as the 2018 shooting in Pittsburgh. In this paper, I will draw examples of Jewish martyrdom starting from the Hasmonean revolt up to the present day.

The Functions

Martyrdom plays a number of important roles within Judaism. Kiddush HaShem can be performed to make a statement of steadfast commitment to Judaism, both to the persecutors and to the martyrs’ peers. This helps keep Judaism alive at the cost of Jewish life. Martyrdom also paints an optimistic side to the great evils persecutors beset Jews with, giving hope to the Jewish community. Martyrdom allows a Jew to avoid committing a grave sin, in which place death is preferable. Commemoration of martyrs can comfort mourners, keep important memories alive, and ground the narrative that forms Jewish culture. Over the centuries, these various purposes shifted as the challenges facing the Jewish community changed. Ultimately, Jewish martyrdom exists for the sanctification of God’s holy name.

In its simplest conception, the option to die al Kiddush HaShem prevented a Jew from committing one of the “Big Three” sins: murder, sexual sin, and idolatry. In a more general scope, Kiddush HaShem allowed for the preservation of Torah, the life-blood of Jewish existence. In the ancient and medieval world, loss of life for the preservation of Torah kept Jewish identity alive for future generations. Moreover, a Jew willing to die in loyalty to God sanctified God’s name in the world. Conversely, a Jew who, for his own life, gave up loyalty to God signaled to the world that God was worth less than a mere human life, thus defiling God’s name. [3]

Martyrdom as a statement in defiance of persecutors can be found all over Jewish history, starting with the Hasmonean revolt. A persecuted Jew could use his martyrdom to transcend the persecutor’s powers. By proclaiming his faith and his God to be greater than his own death, a Jew limited his persecutors’ ability to break the Jew’s will. In the story of a mother and her seven sons, the fifth son belittled his persecutor: “Because you have authority among mortals, though you also are mortal, you do what you please. But do not think that God has forsaken our people. Keep on, and see how his mighty power will torture you and your descendants!” (2 Maccabees 7:16-17).

In the first century, Josephus and Philo wrote about an incident in which Jews unanimously offered themselves up to die before the Roman governor Publius Petronius. Petronius had been ordered to install a statue of Caligula in the Temple. In protest of this abomination, Jews in Ptolemais and Tiberias said that they would die before they saw their laws violated. In Tiberias, the Jews “threw themselves down on their faces and stretched out their throats and said that they were ready to be slain.” This display persuaded Petronius to advocate for the Jews.

A Jewish martyr had the opportunity to set an example for his fellow Jews. In 2 Maccabees 6:18-31, Eleazar, an old man prominent in the Jewish community, refused to eat swine’s flesh. Recognizing his steadfast abstinence, the authorities asked Eleazar to pretend to eat swine’s flesh in front of other Jews. Eleazar refused, fearing that “through my pretense, for the sake of living a brief moment longer, they [young Jews] would be led astray because of me.” The same authorities killed him, making him a martyr in his old age.

In the ancient world, martyrdom tended to challenge the prospect of sinning gravely against God and walking away from Torah. In the medieval world, fear of forced conversion motivated martyrdom. Especially during and after the Crusades, Jews saw in Christian zealots an existential threat by means of conversion. Sefer Hasidim recounts an ambiguous case of attempted self-martyrdom:

There were two who slaughtered themselves but were not able to end their lives, and the Gentiles thought that they were dead even though they were not. Years later they died, and a certain Jew dreamt that those who were actually slain said to them [in paradise], “You shall not enter our company, since you were not killed in sanctification of the name as we were.” They proceeded to show that their necks were cut, but the others responded, “Still, you did not die.” Then an elderly man approached and said: “Because you wounded yourselves with intention to kill and because you were not baptized in their water, it is appropriate for us to be with you.” And they brought them into their company. [4]

The elderly man gives two reasons for considering the two Jews martyrs: 1) they wounded themselves with the intention to kill and 2) they were not baptized Christian. The fear of forced conversion became the primary reason for martyrdom in the middle ages, compelling many to martyr themselves and, in some cases, their own children.

In the twentieth century, the existential crisis to the Jewish people shifted from Torah observance to physical extermination. As such, the definition of martyrdom both expanded and contracted. Yad Vashem considers Holocaust victims “martyrs and heroes,” including secular and converted Jews as martyrs. At the same time, the spiritual implications of martyrdom were put aside for the greater crisis of the Holocaust. As Allen Grossman puts it, “The Holocaust was not a challenge to Jewish martyrdom but an attempt to destroy martyrdom forever,” for “a martyr chooses to die.” [5] With the Holocaust (and post-Holocaust anti-Semitic terrorism), Jewish martyrdom focuses on commemorating and mourning the memory of Jews killed for being Jewish. This concept existed before the Holocaust, but it became dominant afterwards. Thus, the cultural memory of martyrdom generally overrides spiritual or theological considerations.

The Conditions

As noted above, a Jew may opt for martyrdom when faced with the alternative of murder, illicit sex, or idolatry. This basic principle comes from BT Sanhedrin 74a, which states that one may transgress any law of the Torah to save his life, except the “Big Three.” Matters, however, are never so simple. When “in a period of official persecution,” a Jew is expected to commit martyrdom if only to observe a minor mitzvah—“even to change one’s shoe strap.” This makes the requirement to choose martyrdom much more stringent. Jews are to maintain a stubborn observance of Torah when threatened and persecuted; otherwise, they fall down a slippery slope of disregarding the Torah. What’s more, a Jew is to choose martyrdom over violating a minor precept in public so as not to set a bad example or create a sickly environment of communal Torah observance. [6]

R. Ishmael criticizes the requirement to martyr oneself in order to avoid the “Big Three.” He quotes Leviticus 18:5 [7] and argues that “one should live by them [the statutes], and not die by them.” However, R. Akiva’s epic martyrdom has stuck with Jewish tradition as a sort of paradigmatic argument in favor of martyrdom. Papus ben Judah tried to dissuade R. Akiva from teaching the Torah in public, which (according to the Talmud) the Romans punished with death. R. Akiva, however, likened a Jew without Torah as a fish outside of water: Jews need the Torah to live. He used this argument to turn around R. Ishmael’s argument that a Jew should not die by rules of the Torah. Later, when Papus and R. Akiva met in prison, Papus admitted that R. Akiva was right all along, for Papus’ precautions did not save him from Akiva’s fate. Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, writing in the twentieth century, confirms that martyrdom “establishes the veracity of our faith more dynamically than anything else, since one must accept the Torah as absolute Truth to be martyred for it. This commandment applies to all Jews, even children.” [8] Many halakhic considerations surrounding conditions and restrictions of dying al Kiddush HaShem abound, but those presented here are the main principles upon which additional considerations lie.

During the Holocaust, the focus shifted from Torah observance to preservation of life. Yisrael Gutman writes, “The term kiddush ha-hayim (sanctification of life) has in recent years been used to designate the general Jewish stance in the Holocaust.” It is said that Rabbi Yitzhak Nissenbaum, while in the Warsaw Ghetto, ruled that “This is a time for kiddush ha-hayim and not for kiddush ha-Shem through death. In the past, our enemies demanded the Jewish soul and the Jew sacrificed himself through kiddush ha-Shem. Now the enemy demands the Jewish body and the Jew must defend himself and his life!” [9] This attitude exemplifies the Jewish response to the Final Solution. In his responsa, the Orthodox Rabbi Ephraim Oshry allowed fake baptisms, handing children to the care of Christians, and even suicide, given the circumstances of the Holocaust. [10]

From here, one may ask, “Who counts as a Jewish martyr?” Simply, anyone who dies al Kiddush HaShem is counted among the kedoshim. This includes a Jew who dies for the passive status of being Jewish—whether or not he is observant. As Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan puts it, “One who is killed because he is Jewish, even though he is not given any choice, is considered a martyr. Even an evildoer who goes to his death as a Jew sanctifies God and is considered holy.” Similarly, a Jew who has converted out of Judaism may die al Kiddush HaShem. This is not only because someone who has converted out of Judaism retains some degree of Jewish identity, but because Jewish martyrdom (unlike Christian martyrdom) focuses on the act of martyrdom and not the martyred individual. The key here is the sanctification of the holy name—an act and its result. In the rare instance of a non-Jew who was killed for mistakenly being identified as a Jew, such a victim may similarly be considered a kadosh, as he dies at the hands of those who hate God’s people, and such a death is a sanctification of the name. [11] Such victims are not Jewish kedoshim, but they may still be considered kedoshim within Judaism.

[1] “He got under the elephant, stabbed it from beneath, and killed it; but it fell to the ground upon him and he died” (1 Maccabees 6:46).

[2] Shira Lander, “Martyrdom in Jewish Traditions.” Bishops Committee on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs and the National Council of Synagogues.

[3] Solomon Schechter, Julius H. Greenstone, “Martyrdom, Resitriction of.” The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906), accessed online.

[4] Jeremy Cohen, To Sanctify the Name of God. University of Pennsylvania Press (2004). 25. The elderly man’s ruling is consistent with Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s statement: “One who resolves to give his life for God if called upon has the merit of an actual martyr, since God considers a good intention as an accomplished deed” (Kaplan, Handbook of Jewish Thought; full citation in footnote 8).

[5] Grossman, “Holocaust,” in Contemporary Jewish Religious Thought, ed. Cohen and Mendes-Flohr (1987), 406. Quote taken from Shira Lander, “Martyrdom in Jewish Traditions.”

[6] Solomon Schechter, Julius H. Greenstone, “Martyrdom, Restriction of.” The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906), accessed online.

[7] “You shall do my statutes and my judgments which if a person shall do he shall live by them” (Leviticus 18:5).

[8] Aryeh Kaplan, Handbook of Jewish Thought.

[9] For more on the origin and usage of kiddush hachaim, see Yisrael Gutman, “Kiddush Ha-Shem and Kiddush Ha-Hayim.”

[11] Conversation with Shlomo Pill.

Image from British Library, Harley MS 2838 f. 27r.

Leave a Reply