This is a guest post by A Andrew. He is an aspiring Messianic Jewish apologist.

I have lost count of how many times people have pointed to Peter’s vision of the animals on the sheet in Acts 10 and say, “See! You do not need to keep kosher anymore!” It still shocks me every time. The use of Peter’s vision as a proof text for kosher law being discontinued would probably even shock the early Church Fathers. Not even they used Acts 10:9-16 as a justification for their position that no believer should keep kosher [1].

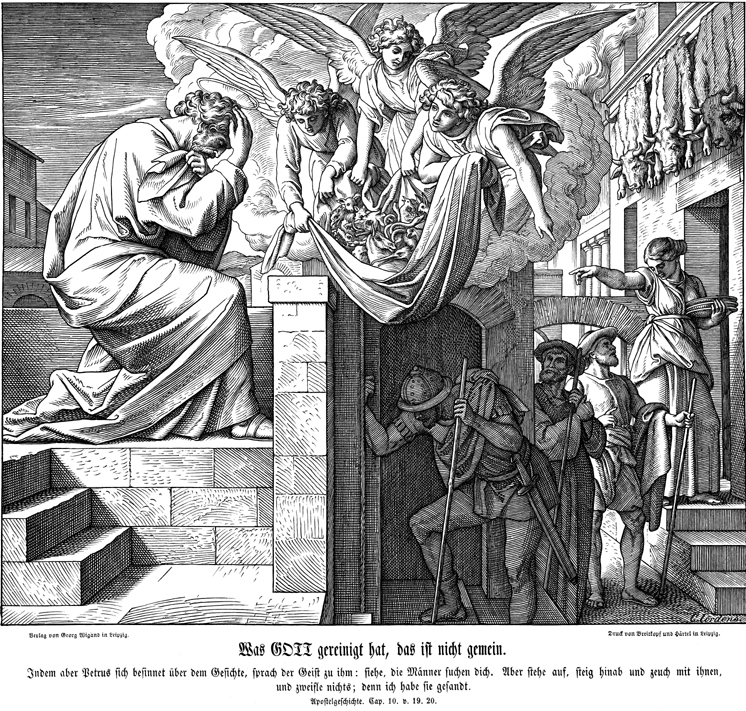

Nonetheless, this objection must still be taken seriously due to its current popularity. Here is the passage in question:

The next day, as the soldiers were traveling and approaching the city, Peter went up to the rooftop to pray, at about the sixth hour. Now he became very hungry and wanted to eat; but while they were preparing something, he fell into a trance. He saw the heavens opened, and something like a great sheet coming down, lowered by its four corners to the earth. In it were all sorts of four-footed animals and reptiles and birds of the air. A voice came to him, “Get up, Peter. Kill and eat.” But Peter said, “Certainly not, Lord! For never have I eaten anything unholy or unclean.” Again a voice came to him, a second time: “What God has made clean, you must not consider unholy.” This happened three times, and the sheet was immediately taken up to heaven.[2]

When reading the passage, we can see how Peter processed this information. He initially reacted in shock by proclaiming, “Certainly not, Lord! For never have I eaten anything unholy or unclean,” which shows that at first, he did interpret it literally. But we can tell that he quickly dismissed that interpretation and began “puzzling about what the vision he had

seen might mean” [3]. This is an indicator that he began pondering a plausible symbolic meaning.

This is the common way in which visions are interpreted in scripture. Jeremiah’s vision of a boiling cauldron tilting to the north was taken as symbolic [4]. Zechariah’s vision of flying scrolls and winged women was symbolic [5]. And Joseph’s vision of the falling stars and the bowing sheaves of wheat was also symbolic [6]. It would really be quite ridiculous to take any of these visions literally. Peter’s reaction to the vision shows that, at first, he reacted to the sheet of clean and unclean animals as meaning to break kosher law as ridiculous and then he began to think seriously about what it might actually mean.

At the same moment he began pondering what the true interpretation of the vision might be, three men from the household of Cornelius came to the gate of the house in which Peter was staying [7]. Cornelius was a Gentile, a centurion, and “a righteous and God-fearing man” who sent these men to Peter because he received a vision from God to do so [8]. The men invited Peter to Cornelius’s house and Peter went without hesitation just as the Holy Spirit instructed [9].

After meeting Cornelius, Peter explained the true interpretation of the vision.

He said to them, “You yourselves know that it is not permitted for a Jewish man to associate with a non-Jew or to visit him. Yet God has shown me that I should call no one unholy or unclean.” [10]

To clarify, when Peter spoke about it not being permitted for a Jew to associate with a non-Jew, he is not referring to a Torah commandment. He is referring to the cultural pressures of his day. David Stern makes this important note about the Greek word that is commonly translated as “not permitted” or “unlawful”:

The word “athemitos,” used only twice in the New Testament, does not mean “unlawful, forbidden, against Jewish law,” as found in other English versions, but rather “taboo, out of question, not considered right, against standard practice, contrary to cultural norms.” [11]

David Stern is not alone in this translation. Notable scholars like F.F. Bruce and Ben Witherington III agree with him [12]. The vision was not telling Peter to disregard a commandment to not associate with a non-Jew. There is no such commandment. Especially, when the non-Jew in question was a “righteous and God-fearing man.”

This description of Cornelius is significant. Being described in this manner places him in a category of people at that time who were known as “God-fearers” [13]. These were Gentiles who worshipped the God of Israel but did not complete a conversion to Judaism by being circumcised. According to Dr. J. Julius Scott Jr., God-fearers even observed the kosher laws [14]. The extent that God-fearers kept the Torah is disputed among scholars, but we know that at the very least, they worshipped the God of Israel and respected Jewish customs and Jewish people.

Even if we are unsure of how God-fearers related to the Torah as an informal group, we have a good idea to what degree Cornelius respected Jewish customs. He was called a God-fearer, he was well-spoken of by all the Jewish people, he prayed the three daily prayers, he gave charity, and when he met Peter he fell at his feet to honor him [15]. These descriptions speak volumes. Cornelius, even if he did not observe kosher law himself, would have been aware of this custom and would have treated his important, Jewish guest with the utmost respect and not prepare an unclean meal.

This raises the question, if God was sending Peter to commune with a Gentile who respected kosher law, what purpose would commanding him to break kosher serve? It would be like your math teacher putting differential equations on the study guide for your final exam, you prepare for it, and then there are no differential equations on the exam. Talk about unnecessary stress. Surely, we should not think that God committed such a blunder.

The evidence does not end there. It is also important to look at the greater context within the book of Acts. A few chapters later, in Acts 15, the Jerusalem Council is meeting in order to officially decide whether Gentiles need to be circumcised. They conclude that they do not, but the Holy Spirit also showed them that Gentiles living among Jewish believers should maintain four essential instructions: abstain from things sacrificed to idols, from sexual immorality, things that are strangled, and from eating blood [16]. What do you notice about these four items? Three of them have to do with food! And they find their foundation in the Torah [17]!

What sense does it make for the Jerusalem Council and the Holy Spirit to conclude that Gentiles living among Jewish believers should uphold some of the food laws if God had just done away with all of the food laws for Jewish believers?

If the traditional Christian interpretation of Acts 10 is correct, then some Gentiles are required to follow some food laws while Jewish believers are not required to follow any.

If Peter had any reason to think that his vision had anything to do with no longer keeping kosher law, the concluding moments of the Jerusalem Council would have been the time to speak up, but there is no record of him doing so.

Again, this leaves us with the conclusion that the most reasonable interpretation of Peter’s vision is solely concerning whether Gentiles have access into the community of God.

I could talk about other powerful and interesting ways to refute the popular, anti-kosher interpretation of Peter’s dream, but I think the case has sufficiently been made. Visions that are described in scripture are consistently given a figurative meaning, Cornelius would not have served an unclean meal to Peter, and the application of a few food laws for some Gentiles would not make any sense if food laws no longer applied to Jewish believers. Not only that, but Peter explicitly gave the correct interpretation of the vision when he says, “Yet God has shown me that I should call no one unholy or unclean.”

Not only do scholars like Michael Brown, David Rudolph, Richard Bauckham, and others agree with this conclusion, but it is likely the early Church Fathers, who were anti-kosher law, would be on the same page [18]. But if anyone remains unconvinced, please let me know! I would love to write about the other powerful ways to refute this common misunderstanding.

[1] David B. Woods, Interpreting Peter’s Vision in Acts 10:9–16. 207.

[2] Acts 10:9-16, Tree of Life Version, referred to as TLV.

[3] Acts 10:17a, TLV.

[4] Jeremiah 1:13-19.

[5] Zechariah 5, this and the Jeremiah example are from Woods’ article as cited in footnote 1, page 179.

[6] Genesis 37:5-11. This example was provided by Jonathan Mann.

[7] Acts 10:17b.

[8] Acts 10:1-8.

[9] Acts 10:19-20.

[10] Acts 10:28, TLV.

[11] David Stern, Jewish New Testament Commentary. 258.

[12] Woods, 183.

[13] Other examples of God-fearers are Lydia (Acts 16:14) and Titius Justus (Acts 18:7).

[14] J. Julius Scott Jr., Jewish Backgrounds of the New Testament. 347.

[15] Acts 10:22-31.

[16] Acts 15:20;29.

[17] Exodus 34:15; Exodus 22:31; Leviticus 3:17.

[18] Michael Brown, Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus Volume 4, 274; For Rudolph, learned from Woods, 185; Richard Bauckham, Introduction to Messianic Judaism: Its Ecclesial Context and Biblical Foundations, edited by David Rudolph and Joel Willits. Chapter 16. 179.

Leave a Reply