I want to begin my exploration of chaplaincy by recounting a story from the Talmud (Shabbat 33b:5-8). The story tells of the holiness of secular observance.* In a time when devoted Christians rightly contemplate the Benedict Option, this Jewish story may serve as an important reminder not to abandon the world God has placed us in.

The Bar Kochba revolt (132-136 AD) against Roman occupiers ended in one of the greatest catastrophes for the Jews of the ancient world. A revered rabbi named Rabbi Akiva had made himself the spiritual leader of this revolt, even declaring Shimon bar Kochba to be Messiah! Many thousands of Jews were killed, and this time the Romans decided to suppress the Judaism of the rabbis. They killed Rabbi Akiva, along with nine other prominent rabbis who became martyrs in Jewish tradition.

But Rabbi Akiva’s followers survived him. One of them was Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. Rabbi Shimon, as you can imagine, did not much like the Romans. At one point, he decried local Roman developments: “Everything that they [Romans] established, they established only for their own purposes. They established marketplaces, to place prostitutes in them; bathhouses, to pamper themselves; bridges, to collect taxes from [all who pass over] them.” This statement eventually reached the ears of the Roman overlords. They declared that Rabbi Shimon must be killed for his rebellious words.

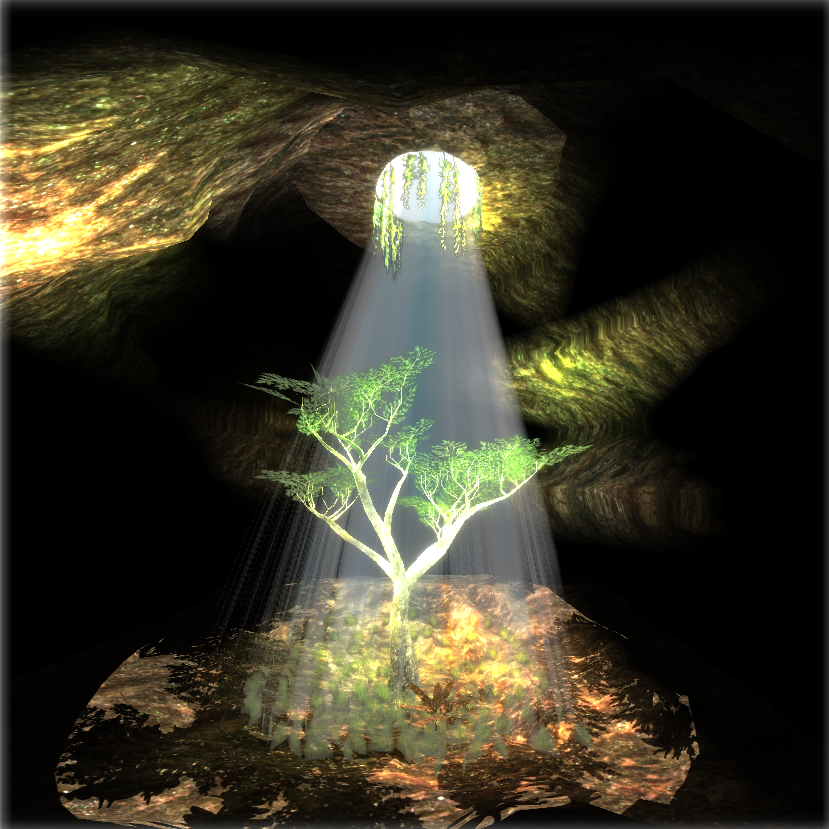

Rabbi Shimon and his son (Rabbi Elazar) hid in a cave. (Talk about living under a rock!) In the cave, God provided for them by growing a carob tree and causing a spring of water to flow through the cave. For their part, Rabbi Shimon and his son lived as piously as they could. To preserve their clothes for the three daily times of prayer, they remained naked for the rest of the day. They lived this way for twelve years. Isolated from the world and living by God’s miraculous provision, they became increasingly detached from the world and grew in mystical holiness.

One day, they overheard the prophet Elijah say that the Roman emperor had died and Rabbi Shimon could now safely come out of hiding. So Rabbi Shimon and his son came out. But when they saw people going about normal secular life—plowing and sowing—they were disappointed. Rabbi Shimon said that these secular people “abandon eternal life and engage in temporal life.” Having survived for twelve years by God’s miraculous provision, Rabbi Shimon felt the Jews’ priorities were misaligned. The mystical holiness Rabbi Shimon had developed in the cave could not coexist with the secular life of the local agriculturalists. In fact, everything Rabbi Shimon and his son directed their eyes at was immediately incinerated! This became such a disaster that a voice from heaven intervened, asking them, “You emerge [from the cave only] to destroy My world? Return to your cave.”

Rabbi Shimon and his son obeyed. They sat in the cave for another twelve months as penance. After twelve months, the voice from heaven told them to emerge from the cave. This time, Rabbi Shimon’s son continued in his destructive condemnation of secular life, but Rabbi Shimon fixed everything his son destroyed. Rabbi Shimon tried to explain to his son that they need not condemn those occupied with secular life, for the piety of Rabbi Shimon and Rabbi Elazar sufficed for the whole world.

One Friday afternoon, the rabbis came upon an old man running home to arrive in time for Shabbat. This man held two bundles of myrtle branches in his hands. He explained to the rabbis that one bundle corresponded to the command to remember the Shabbat (Exodus 20:8) and the other corresponded to the command to observe the Shabbat (Deuteronomy 5:12).

Carrying bundles of myrtle branches is not a typical ritual for observing Shabbat. But this old man’s creative observance and his explanation showed the rabbis that even in a secular agricultural setting he devoted his thoughts to Torah study and observance. Rabbi Shimon and his son were satisfied when they witnessed this old man’s faithfulness and they no longer worried over their fellow Jews’ apparent preoccupation with secular life.

The word “secular,” coming from Latin “saeculum” (“age, generation”), refers to the transitory nature of worldly matters. Rabbi Shimon’s initial concern that people “abandon eternal life and engage in temporal life” ought to be taken seriously. At the same time, as Pascal observed, man has been placed between the infinitesimal and infinity (“Man’s disproportion,” Pensées, 199/72). Stuck in this awkward position, the old man carrying two bundles of myrtles had nevertheless found a way to engage with the eternal in a simple, earthy way—a way God had provided for him. The heavenly voice proclaimed Creation as God’s world, and the old man in his faithful observance devoted his secular life, along with Creation, to God.

This story shows us the great value of sanctifying the secular world through intentional observance. At a time when pious Christians are tempted to withdraw from the secular world, chaplains may play an increasingly important role in restoring and catalyzing religious devotion in secular spaces.

*By “secular,” I do not mean “godless,” a usage from the 1850s; I use the word in its medieval meaning of “not pertaining to religious occupation.”

Leave a Reply