In writing this article, I want to clarify any misconceptions that I may generate upfront. I am not arguing against mortification itself. I am not arguing against the practice of what I will call “continuous mortification” for some if not most Christians. What I am thinking through is the notion that continuous mortification is not necessary for all Christians at all times.

In some definitions, mortification is a method used by Christians to contract the corruption of our past life of sin and raise us to a new life in Christ. Specifically, this method uses physical or mental approaches of disciplines to grow closer to God and avoid sin. Fasting, long meditation, rocks in your shoe, cold showers, and sleeping on a hard surface are all forms of mortification.

From what I have read it seems there are two purposes of mortification: to avoid sin and to love God. Mortification to avoid sin is necessary to ensure we have enough control over our flesh and is always a good; as sin is always an evil. However, mortification to love God is the practice of mortification out of a love for the cross. This type of mortification is not for everyone. Rather, it requires serious discernment with a spiritual director, for it can even lead individuals into deep sin. For this reason, continuous mortification, or the practice of mortification regularly throughout your life, is not a universally good practice (but a particular one).

Before diving into mortification, here is a passage in the catechism on the importance of interior penance (including mortification!):

Jesus’ call to conversion and penance, like that of the prophets before him, does not aim first at outward works, “sackcloth and ashes,” fasting and mortification, but at the conversion of the heart, interior conversion. Without this, such penances remain sterile and false; however, interior conversion urges expression in visible signs, gestures and works of penance. Interior repentance is a radical reorientation of our whole life, a return, a conversion to God with all our heart, an end of sin, a turning away from evil, with repugnance toward the evil actions we have committed. At the same time it entails the desire and resolution to change one’s life, with hope in God’s mercy and trust in the help of his grace. This conversion of heart is accompanied by a salutary pain and sadness which the Fathers called animi cruciatus (affliction of spirit) and compunctio cordis (repentance of heart). (CCC, 1430-31)

Imagine the hurt you feel when, after a spout of anger, you realize that you have deeply hurt someone you care about. This pain is analogous to the sorrow we have at each of our own sins before God. Appreciating the depth of our own evil necessitates that conversion is not a “sterile” intellectual process but deeply emotional and personal. Only after such conversion does mortification take on any meaning and aid to our spiritual life. As we turn away from evil and strive to avoid sin, mortification can help us build discipline to get rid of bad habits and routines. At this point, mortification out of a love for God comes.

Now, it should be obvious that loving God is always good. However, I will posit that sometimes what we perceive as loving God may be a guise for pride in our own self-righteousness. As we move and build habits that mitigate the influence of sins of the flesh, we are at increasing risk of falling into pride. Conducting disciplines and mortifications in private goes a long way in helping prevent the buildup of this pride, yet it is still possible to feel pride in our hearts and place ourselves above those around us we deem as “worse” sinners. Taking on greater and greater mortifications regularly can begin to transform into a sin of pride and lack of obedience to God.

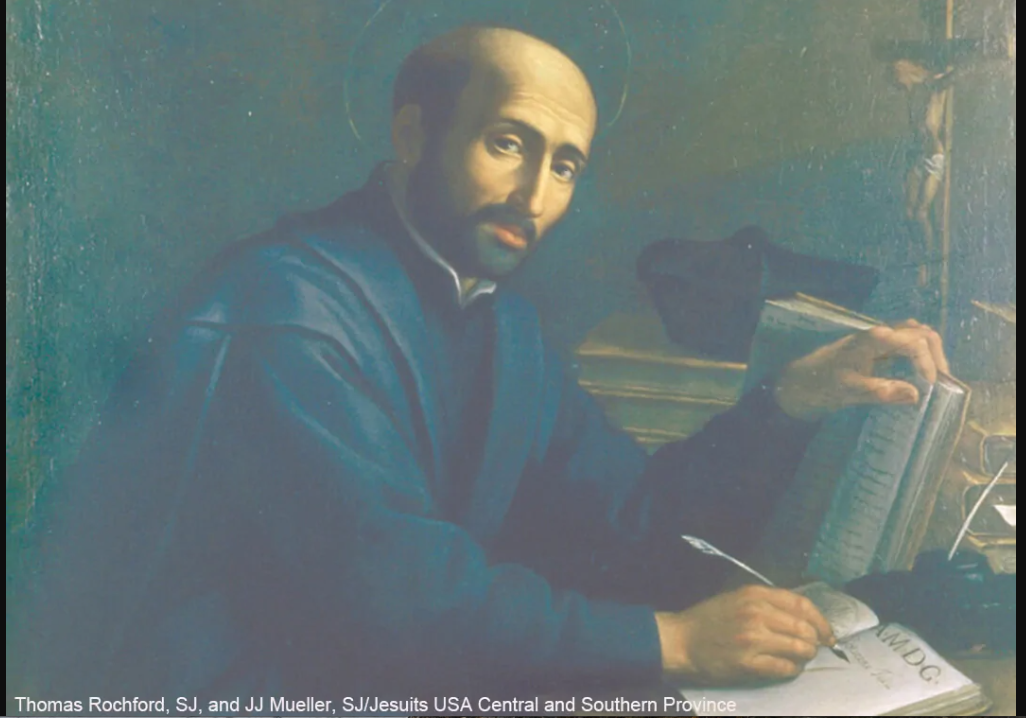

In thinking about this article, I went through a couple of St. Ignatius of Loyola’s letters and found some helpful gems. Most pertinent was a letter St. Ignatius wrote to Stephano Casanova who would mortify most, if not all, cravings to the harm of his own health:

Moreover, this repressing can be of two sorts. One is when through reason and light from God you become aware of a movement of sensuality or of the sensitive faculty which is against God’s will and would be sinful, and you repress this out of the fear and love of God. This is the right thing to do even if weakness or any other bodily ill ensues, since we may never commit any sin for this or any other consideration. But there is another kind of repressing one’s sensuality, when you feel a desire for some recreation or anything else that is lawful and entirely without sin, but out of a desire for mortification or love of the cross you deny yourself what you long for. This second sort of repression is not appropriate for everyone, nor at all times. In fact, there are times when in order to sustain one’s strength over the long haul in God’s service, it is more meritorious to take some honest recreation for the senses than to repress them. And so you can see that the first sort of repression is good for you, but not the second—even when you aim at proceeding by the way that is most perfect and pleasing to God.

Ignatius of Loyola brings up how one should not necessarily engage in the second source of repression. For some, it may be good, but not as much for others. He addresses how damaging one’s health could be problematic and not pleasing to God. Yet for some readers, a slightly worse-off health may not seem that big a deal. That is why I wanted to dive into situations where visible mortification was in reality demonic rather than divine.

On a more personal note, what initially prompted me to write this article is an instinctive feeling that a strong personal focus on mortification and one’s own spiritual life could lead to an over-focus on the self. I have held that Christ’s commands to love God and our neighbor implies a sort of radical self-detachment that Christians should all aspire towards. (Not self loathing, but rejecting egotism). For me, I have noticed that as I build up specific spiritual disciplines or undertake mortifications, the process feels very self-focused. Growth in the spiritual life is good, as is mortification! But I worry that too strong a focus on our own growth and mortification can lead us to pride and a rejection of a Christ-centered life. However, realizing that we are not meant to walk without community, having a spiritual director or mentor is essential for discerning these questions. To end how St. Ignatius ended his letter,

For further particulars, I refer you to your confessor, to whom you will show this letter, and I commend myself to your prayers.

Leave a Reply