When looking at the Old Testament, Christians often like to focus on the stories of the Patriarchs and the Exodus, the epic miracles of the judges and prophets, or the poetry found in the Books of Wisdom. This usually leaves large parts of the Law and the Histories as the butt of jokes about the “boring but sacred” parts of the Bible.*

The anecdotes of Joshua conquering Jericho, David slaying Goliath, and Elijah’s showdown on Mount Carmel are well known for their exciting miracles and morals. But today I want to focus on the “boring” parts of the Histories: those parts rife with tediously repetitive genealogies, unfamiliar names that embarrass readers at Bible studies, and depressing records of bad kings.

First and 2 Chronicles span from Adam to Zedekiah, giving us a broad generational view of the Israelites. One can often find a summary of a king’s reign at the end of a royal biography. Such a summary generally includes a final moral assessment of the king. Saul “was unfaithful to the Lord; he did not keep the word of the Lord” (1 Chronicles 10:13). Amaziah “did what was right in the sight of the Lord, yet not with a true heart” (25:2). Jehoram “passed away, to no one’s regret” (21:20).

The Histories put into spotlight a Biblical theme that is ignored in modern American culture: the importance of inter-generational faithfulness. Often, we find the kings being compared with each other. Ahaziah “did what was evil in the sight of the Lord, as the house of Ahab had done; for after the death of his father they were his counselors, to his ruin” (22:4). Elijah rebuked Jehoram for not walking “in the ways of [his] father Jehoshaphat or in the ways of King Asa of Judah” (21:12). These inter-generational comparisons form an important theme in the Histories. If a king emulates those in his lineage who had lived closely to God, he is praised. If he follows in the evil ways of previous monarchs, the chronicler denounces his reign. The kings desperately needed to improve upon their preceding generations.

Looking at high-power figures from a generational perspective allows us to see the influence one generation has upon another. It reveals the responsibility a ruler has in setting a good example for future generations, and for redeeming the kingdom from the evils of previous generations.

“A good leader creates followers, but a great leader creates leaders.”

–Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks

One of the tragedies of the Histories is the rarity of good rulers passing their righteousness on to posterity. The elders of Israel asked Samuel for a king because Samuel’s sons were corrupt and did not follow in their father’s ways (1 Samuel 8:1-5). Although Solomon ruled wisely in his youth, “when Solomon was old… his heart was not true to the Lord his God, as was the heart of his father David… So Solomon did what was evil in the sight of the Lord, and did not completely follow the Lord, as his father David had done.” (1 Kings 11:4, 6). While every generation can make itself a great generation, the true challenge lies in facilitating the perpetuation of faithfulness.

“Après moi, le déluge.” [After me, the storm.] –King Louis XV

Such was the tragedy of Hezekiah who, despite being a relatively righteous king, did not look to the continuation of his legacy beyond his own life:

“Days are coming when all that is in your house, and that which your ancestors have stored up until this day, shall be carried to Babylon; nothing shall be left,” says the Lord. “Some of your own sons who are born to you shall be taken away; they shall be eunuchs in the palace of the king of Babylon.” Then Hezekiah said to Isaiah, “The word of the Lord that you have spoken is good.” For he thought, “Why not, if there will be peace and security in my days?” 2 Kings 20:17-19

Hezekiah struggled with pride (2 Chronicles 32:25), and destruction followed his reign. And this destruction is rightfully held against Hezekiah for his self-centered approach to rulership.

Inter-generational faithfulness means 1) looking out for the well-being of the next generation and 2) redeeming one’s own lineage by improving upon previous generations. This outlook accepts the imperfections of one’s origins while also allowing hope for the future.

Still, every generation is responsible for its own record. Second Chronicles 25: 3-4 tells us about the manner in which Amaziah carried out justice:

As soon as the royal power was firmly in his hand he killed his servants who had murdered his father the king. But he did not put their children to death, according to what is written in the law, in the book of Moses, where the Lord commanded, “The parents shall not be put to death for the children, or the children be put to death for the parents; but all shall be put to death for their own sins.”

Chronicles acknowledges that each individual is punished for his own sin. The choice to remain faithful to the covenant with God is a choice every generation makes for itself. Even so, this does not negate the responsibility for inter-generational faithfulness. Part of our covenant with God is a promise to do our best to teach God’s laws to our children (Deuteronomy 11:9).

Give ear, O my people, to my teaching;

incline your ears to the words of my mouth.

I will open my mouth in a parable;

I will utter dark sayings from of old,

things that we have heard and known,

that our ancestors have told us.

We will not hide them from their children;

we will tell to the coming generation

the glorious deeds of the Lord, and his might,

and the wonders that he has done.Psalm 78:1-4, a maskil of Asaph

* I would postulate that a slight interest in the Law has been developing among Christians, if only because Atheists like to nitpick individual laws to make sweeping claims against the morals of the Bible.

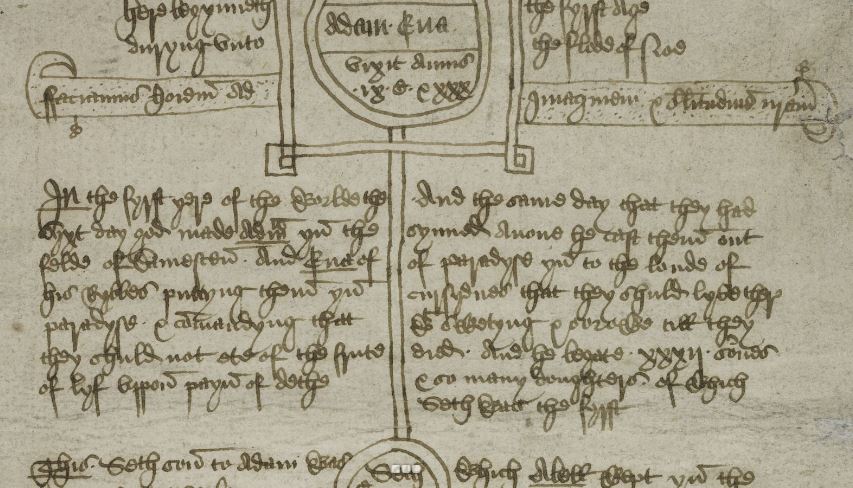

The scanned manuscript featured at the top of this post is a Genealogical Chronicle, starting with Adam and Eve. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 546. Image taken from the Parker Library on the Web.

Leave a Reply